The Marinelli Foundry of Florence

An Overview

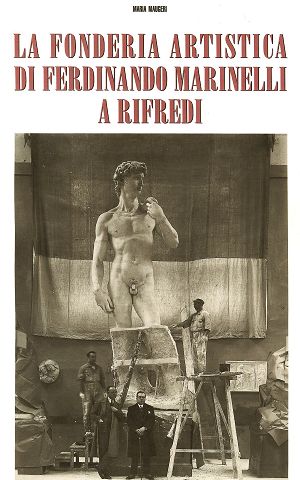

The Ferdinando Marinelli foundry represents the twentieth-century chapter of an age-old story, the Tuscan genius for casting bronzes. Long before the Romans came to this region, the Etruscans actively mined and smelted its rich deposits of copper, lead, and iron ore. They fabricated bronze from a metal alloy of copper and tin. More adaptable than stone, and more durable, bronze was valued only slightly less than gold and silver. Etruscan artisans excelled at casting bronze ornaments, statues and mirrors. Their example was followed and developed by the Roman founders of the city named Florentia. The ancients’ bronzes and their lost-wax method were rediscovered by the Renaissance and never again forgotten. Not by chance, the first chapter of Maria Maugeri’s history of the Marinelli foundry, La Fonderia Artistica di Ferdinando Marinelli a Rifredi (Florence, 2003), is dedicated to these beginnings, more than a thousand years ago. Now in its third revised edition, Maugeri’s admirable book is warmly recommended for its illustrations and documentation of the events and projects that will be mentioned in this introduction.

The Ferdinando Marinelli foundry represents the twentieth-century chapter of an age-old story, the Tuscan genius for casting bronzes. Long before the Romans came to this region, the Etruscans actively mined and smelted its rich deposits of copper, lead, and iron ore. They fabricated bronze from a metal alloy of copper and tin. More adaptable than stone, and more durable, bronze was valued only slightly less than gold and silver. Etruscan artisans excelled at casting bronze ornaments, statues and mirrors. Their example was followed and developed by the Roman founders of the city named Florentia. The ancients’ bronzes and their lost-wax method were rediscovered by the Renaissance and never again forgotten. Not by chance, the first chapter of Maria Maugeri’s history of the Marinelli foundry, La Fonderia Artistica di Ferdinando Marinelli a Rifredi (Florence, 2003), is dedicated to these beginnings, more than a thousand years ago. Now in its third revised edition, Maugeri’s admirable book is warmly recommended for its illustrations and documentation of the events and projects that will be mentioned in this introduction.

In 1919, the year that Ferdinando Marinelli opened his own bronze foundry in Rifredi, a new commercial zone on the north side of the city center, Florence was well established as a center for highly skilled industrial metal casting. Marinelli was born in 1887 near Perugia. He came to Florence as a boy to begin his years of apprenticeship. He trained at the well-known Vignali foundry, which cast the sculptures for many leading artists of the nineteenth century. At the time it was customary for bronze foundries to accept every kind of project, large and small, often connected with architectural fittings. When later Marinelli inserted the word ‘artistica’ – in the name of his foundry, it would serve to indicate that its products were superior to industrial quality. Marinelli’s ‘Fonderia Artistica’ would specialize in bronzes by contemporary sculptors as well as meet the thriving demand for art-quality replicas of ancient and Renaissance masterpieces. The nineteenth century had a high regard for the Renaissance skills of replicating sculptures by plaster casts that can be copied in marble or in bronze, preferably with the lost-wax method.

In 1919, the year that Ferdinando Marinelli opened his own bronze foundry in Rifredi, a new commercial zone on the north side of the city center, Florence was well established as a center for highly skilled industrial metal casting. Marinelli was born in 1887 near Perugia. He came to Florence as a boy to begin his years of apprenticeship. He trained at the well-known Vignali foundry, which cast the sculptures for many leading artists of the nineteenth century. At the time it was customary for bronze foundries to accept every kind of project, large and small, often connected with architectural fittings. When later Marinelli inserted the word ‘artistica’ – in the name of his foundry, it would serve to indicate that its products were superior to industrial quality. Marinelli’s ‘Fonderia Artistica’ would specialize in bronzes by contemporary sculptors as well as meet the thriving demand for art-quality replicas of ancient and Renaissance masterpieces. The nineteenth century had a high regard for the Renaissance skills of replicating sculptures by plaster casts that can be copied in marble or in bronze, preferably with the lost-wax method.

Despite, or rather because of, the city’s prominence during the Renaissance, nineteenth-century Florence was a beacon for expatriate sculptors, especially Americans, who wished to perfect their art through knowledge of the past. Boston native Horatio Greenough settled in Florence in 1828, remaining until 1851. Greenough established the tradition of Italian study for American sculptors, which was followed by every noted artist, but especially Hiram Powers, who also moved permanently to Florence. Powers shipped sculptures of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin to the United States Capitol and to several statehouses for permanent display. Nathaniel Hawthorne immortalized the American artists’ colony in his novel, The Marble Faun. For artists and writers of the nineteenth century, the creations of Greek and Roman antiquity represented the unchallenged pinnacle of art, embodying principles of harmony, nobility, and permanence that, according to one critic, attained ‘that perfection which is today our model and our despair’. Even with the waning of neoclassical style around the turn of the twentieth century, art-quality bronze casts of the masterpieces in the Florentine museums were in demand worldwide.

Despite, or rather because of, the city’s prominence during the Renaissance, nineteenth-century Florence was a beacon for expatriate sculptors, especially Americans, who wished to perfect their art through knowledge of the past. Boston native Horatio Greenough settled in Florence in 1828, remaining until 1851. Greenough established the tradition of Italian study for American sculptors, which was followed by every noted artist, but especially Hiram Powers, who also moved permanently to Florence. Powers shipped sculptures of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin to the United States Capitol and to several statehouses for permanent display. Nathaniel Hawthorne immortalized the American artists’ colony in his novel, The Marble Faun. For artists and writers of the nineteenth century, the creations of Greek and Roman antiquity represented the unchallenged pinnacle of art, embodying principles of harmony, nobility, and permanence that, according to one critic, attained ‘that perfection which is today our model and our despair’. Even with the waning of neoclassical style around the turn of the twentieth century, art-quality bronze casts of the masterpieces in the Florentine museums were in demand worldwide.

After a hiatus during World War I, when European governments prohibited artistic casting because the metal was needed for war materiel, Marinelli expanded his offerings to the wider public, entering into partnership with an art gallery. In June 1924 Marinelli sold a bronze replica of Verrocchio’s famous Putto with a Dolphin, which was offered as the prize of a lottery to benefit the relief and reconstruction of Dalmatia. Verrocchio’s light-hearted interpretations were evidently the first to attract favor. In 1927, Marinelli received the considerable fee of 7800 Lire from the city of Liege, France, for a life-sized cast of Verrocchio’s David in the National Museum of the Bargello. Business of this sort continued to expand during the economic recovery of the 1920s – and so did the Marinelli catalogue of available casts. The Accademia in Florence had acquired high quality plaster casts of important sculptures in the city. Some bronze casters owned a scattering of plasters, some taken from the originals, others made from copies. Amongst the private foundries, Marinelli stood out from the beginning for constantly seeking to build a collection of original plaster prototypes as opposed to copies of other casts. Casts, like photographic negatives, have more detail in the prototype than in the copy. Whenever the city’s Fine Arts authority employed Marinelli to clean the bronze and marble treasures exposed in the open air, he always obtained permission to take plaster prototypes and the right to cast from them.

The Marinelli foundry was singled out for its high standards in a 1927 report by the Chamber of Commerce of Florence, which concludes, “it owes its renown to the perfection of its casting techniques which permit a system of patina or coating by acids designed to allow the metal to be left uncovered and not lose any of its reflective properties. The warm tonality of natural bronze contributes greatly to the artistic quality.” Marinelli continued to experiment with refinements on the ‘lost wax’ technique that he had inherited from the Renaissance. He obtained an original cast of the Doors of Paradise by Ghiberti in the course of a commission to clean them for the city.

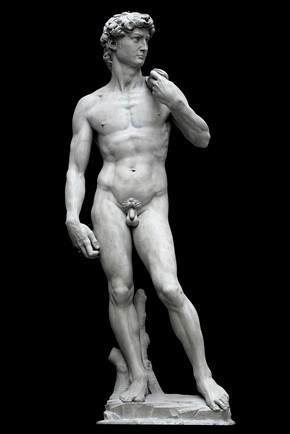

In 1929 a commission from the consul of Uruguay, Gilberto Fraschetti, involved the Marinelli foundry in a principal role in the ongoing story of the most important artistic monument ever replicated in life-sized bronze: the David of Michelangelo. The story of casting this great statue begins in 1846 when Leopoldo II, grand duke of Tuscany, ordered a cast taken and placed in the Loggia dei Lanzi. The cast was later transferred to the Accademia and then, briefly, to the Bargello museum. The purpose of these moves was to test the definitive new site for the original David in the piazza della Signoria. Michelangelo’s statue was showing signs of abrasion from the elements and had to be taken indoors. Through the years, the duke authorized plaster casts as gifts for Queen Victoria’s Victoria and Albert Museum in London and for the German government. A bronze cast of David’s head was exhibited in the Paris Exposition of 1855. In 1873 a full-sized bronze David was installed as the centerpiece of the Piazzale Michelangelo, the city’s most beautiful panorama. Today it is a popular meeting place and monument in its own right. The plaster cast of 1846 created by Leopoldo II no longer existed in 1929 and the Florentine authorities were pleased to cooperate with the Marinelli commission from the government of Uruguay. Marinelli technicians made two life sized plaster casts of the David, one for deposit in the Gipsoteca, the municipal collection of casts, and one for the firm’s collection. The Gipsoteca model was invaluable in the restoration of the Michelangelo’s original in the Accademia after its attack in 1991. Marinelli’s bronze replicas of the David, Donatello’s Gattamelata, and Verrocchio’s Colleoni, both Renaissance equestrian monuments, were sent to Montevideo.

In 1929 a commission from the consul of Uruguay, Gilberto Fraschetti, involved the Marinelli foundry in a principal role in the ongoing story of the most important artistic monument ever replicated in life-sized bronze: the David of Michelangelo. The story of casting this great statue begins in 1846 when Leopoldo II, grand duke of Tuscany, ordered a cast taken and placed in the Loggia dei Lanzi. The cast was later transferred to the Accademia and then, briefly, to the Bargello museum. The purpose of these moves was to test the definitive new site for the original David in the piazza della Signoria. Michelangelo’s statue was showing signs of abrasion from the elements and had to be taken indoors. Through the years, the duke authorized plaster casts as gifts for Queen Victoria’s Victoria and Albert Museum in London and for the German government. A bronze cast of David’s head was exhibited in the Paris Exposition of 1855. In 1873 a full-sized bronze David was installed as the centerpiece of the Piazzale Michelangelo, the city’s most beautiful panorama. Today it is a popular meeting place and monument in its own right. The plaster cast of 1846 created by Leopoldo II no longer existed in 1929 and the Florentine authorities were pleased to cooperate with the Marinelli commission from the government of Uruguay. Marinelli technicians made two life sized plaster casts of the David, one for deposit in the Gipsoteca, the municipal collection of casts, and one for the firm’s collection. The Gipsoteca model was invaluable in the restoration of the Michelangelo’s original in the Accademia after its attack in 1991. Marinelli’s bronze replicas of the David, Donatello’s Gattamelata, and Verrocchio’s Colleoni, both Renaissance equestrian monuments, were sent to Montevideo.

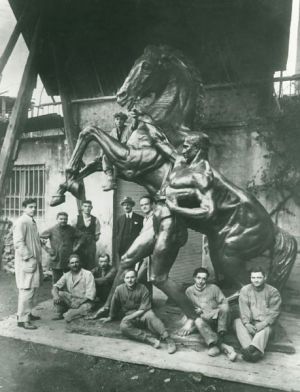

The enthusiastic response to these arrivals in the Uruguay capital led directly to the commission to cast a huge sculptural group representing a pioneer wagon train as designed by the sculptor J. Belloni. Twenty five yards in length and weighing 15 tons, this wagon and straining team of oxen is one of the twentieth century’s outstanding original bronze sculptures and has become a national symbol.

The 1930s were a particularly active decade for public monuments. In 1932, the Marinelli firm entered into an important and enduring relationship with the Vatican with the commission for bronze reliefs on the grand elliptical staircase of the new entrance of the Vatican museums. The foundry would also cast the bronze casket of Pope Pius XI, designed by Antonio Berti, and the Porta Santa, “Holy Door”, at the right side of St. Peter’s, designed by artist Vico Consorti. The foundry was constantly engaged in casting monumental doors for such basilicas as Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome and the cathedrals of Siena, Oropa, and Sassari, not to mention Bogotà in Colombia. The special relationship with the Vatican made it possible for Ferdinando Marinelli to take a plaster cast from Michelangelo’s Pietà in St Peter’s, Rome. It was the kind of privilege that is unthinkable today.

The enthusiasm for public works called beneficial attention to the Renaissance monuments of Florence. A state visit of 1938 was the occasion for the restoration of the bronzes in the piazza della Signoria and the niches outside the Or San Michele church in Florence. The Marinelli firm acquired the plaster prototypes after cleaning the four sea-gods around the fountain by Ammanati and three bronzes by Donatello, the Marzocco, the San Ludovico and the Judith and Holofernes.

After the interruption of the war years, and the ensuing economic crisis in Italy, the Marinelli foundry resumed its previous levels of production. In 1945, Ferdinando Marinelli, now ailing, passed the direction over to his two sons Aldo and Marino. The Marinelli Fonderia artistica played a leading role in the creation of sculptures in commemoration of the soldiers and civilians who lost their lives in World War II. The government of Italy commissioned Leo J. Friedlander’s bronze Sacrifice, a huge equestrian composition, that was sent to the United States in 1951 and placed at the entrance to the bridge of Arlington Memorial Cemetary. Noted sculptor Robert Dean’s portrait of General Eisenhower was cast in Florence and installed in Grovesnor Square, London, across the street from Ike’s World War II headquarters. Two other memorial sculptures worth special mention are the bronze urns with allegorical reliefs designed by Donald De Lue, the foremost specialist in American military commemorative statues. These large bronze urns are decorated with allegories of the valor of the fallen soldiers and the suffering of the innocent. They stand in the two loggias at the entrance to the Normandy American Cemetery on the cliff above Omaha Beach.

After the interruption of the war years, and the ensuing economic crisis in Italy, the Marinelli foundry resumed its previous levels of production. In 1945, Ferdinando Marinelli, now ailing, passed the direction over to his two sons Aldo and Marino. The Marinelli Fonderia artistica played a leading role in the creation of sculptures in commemoration of the soldiers and civilians who lost their lives in World War II. The government of Italy commissioned Leo J. Friedlander’s bronze Sacrifice, a huge equestrian composition, that was sent to the United States in 1951 and placed at the entrance to the bridge of Arlington Memorial Cemetary. Noted sculptor Robert Dean’s portrait of General Eisenhower was cast in Florence and installed in Grovesnor Square, London, across the street from Ike’s World War II headquarters. Two other memorial sculptures worth special mention are the bronze urns with allegorical reliefs designed by Donald De Lue, the foremost specialist in American military commemorative statues. These large bronze urns are decorated with allegories of the valor of the fallen soldiers and the suffering of the innocent. They stand in the two loggias at the entrance to the Normandy American Cemetery on the cliff above Omaha Beach.

At home, a Marinelli replica of Pietro Tacca’s Renaissance sculpture of a giant boar is one of Florence’s most beloved monuments. Positioned under the arches of the central marketplace, known as the Mercato Nuovo, with a stream of water issuing from its mouth, the Porcellino is Florence’s Trevi fountain. Every year thousands of tourist families rub its shiny snout and make a wish to return someday. People naturally assume that the replica is Tacca’s original, which stood in this place for centuries but is now preserved inside the Bargello museum. Tacca, an outstanding pupil of the great Giambologna, cast his original between 1612 and 1630. He took his inspiration from a classical Roman marble of a wild boar resting on his hindquarters, a work that was celebrated in the Medici collections (today in the Uffizi galleries) for its rarity. Tacca embellished the piece, with a marvelous base that teems with flora and fauna. Through the years the Marinelli foundry has executed replicas of Tacca’s Porcellino to the Louvre Museum in Paris, Waterloo University in Canada, and sites in Australia and California. Recently, the Marinelli foundry was called upon by the city of Livorno to remedy an ancient ‘injustice’ regarding a Tacca masterpiece. The fanciful Triton fountains in the piazza SS. Annunziata were originally destined for Livorno on the seacoast, but were kept for Florence by the Grand Duke after admiring their beauty. Centuries later, Livorno has its pair of Triton fountains in the form of Marinelli replicas.

At home, a Marinelli replica of Pietro Tacca’s Renaissance sculpture of a giant boar is one of Florence’s most beloved monuments. Positioned under the arches of the central marketplace, known as the Mercato Nuovo, with a stream of water issuing from its mouth, the Porcellino is Florence’s Trevi fountain. Every year thousands of tourist families rub its shiny snout and make a wish to return someday. People naturally assume that the replica is Tacca’s original, which stood in this place for centuries but is now preserved inside the Bargello museum. Tacca, an outstanding pupil of the great Giambologna, cast his original between 1612 and 1630. He took his inspiration from a classical Roman marble of a wild boar resting on his hindquarters, a work that was celebrated in the Medici collections (today in the Uffizi galleries) for its rarity. Tacca embellished the piece, with a marvelous base that teems with flora and fauna. Through the years the Marinelli foundry has executed replicas of Tacca’s Porcellino to the Louvre Museum in Paris, Waterloo University in Canada, and sites in Australia and California. Recently, the Marinelli foundry was called upon by the city of Livorno to remedy an ancient ‘injustice’ regarding a Tacca masterpiece. The fanciful Triton fountains in the piazza SS. Annunziata were originally destined for Livorno on the seacoast, but were kept for Florence by the Grand Duke after admiring their beauty. Centuries later, Livorno has its pair of Triton fountains in the form of Marinelli replicas.

From the Parthenon, to the David, to the Statue of Liberty, to the Sydney Opera House, distinguished sculptures and buildings have always defined the character of their cities. In modern times, Marinelli bronzes have done their part in too many locations to name here, but we can conclude with two contemporary American cities, San Diego and Denver. Remarkably, the two commissions were the inspiration of the same patron, Pat Bowlen. In 1982, Bowlen acted on the advice of a Florentine friend and commissioned from sculptor Sergio Benvenuti, the Two Oceans Fountain, that is a popular landmark in San Diego. Twenty years later, the same Florentine, Dudi Berretti, advised Bowlen to commission the same master, Benvenuti, to create a spectacular sculpture group for the south entrance of the new stadium of the Denver Broncos. The work, “Broncos” consists of five stallions, a mare and a colt that are shown in full gallop up an incline hill that runs with a swiftly flowing fountain. The seven bronze horses, each over life-sized and weighing 1.2 to 2 tons, was unveiled in August 2001 and was an overnight tourist attraction of the Mile High City.

From the Parthenon, to the David, to the Statue of Liberty, to the Sydney Opera House, distinguished sculptures and buildings have always defined the character of their cities. In modern times, Marinelli bronzes have done their part in too many locations to name here, but we can conclude with two contemporary American cities, San Diego and Denver. Remarkably, the two commissions were the inspiration of the same patron, Pat Bowlen. In 1982, Bowlen acted on the advice of a Florentine friend and commissioned from sculptor Sergio Benvenuti, the Two Oceans Fountain, that is a popular landmark in San Diego. Twenty years later, the same Florentine, Dudi Berretti, advised Bowlen to commission the same master, Benvenuti, to create a spectacular sculpture group for the south entrance of the new stadium of the Denver Broncos. The work, “Broncos” consists of five stallions, a mare and a colt that are shown in full gallop up an incline hill that runs with a swiftly flowing fountain. The seven bronze horses, each over life-sized and weighing 1.2 to 2 tons, was unveiled in August 2001 and was an overnight tourist attraction of the Mile High City.

By the end of the twentieth century, the Marinelli foundry had produced more art bronzes than any other Florentine workshop, which is still a family enterprise personally overseen by the grandson of the founder, Ferdinando Jr. At the beginning of this short piece, I remarked that the Marinelli foundry represents the twentieth-century chapter of an age-old story: as we have seen, the foundry embodies in fact three centuries in all: the nineteenth, when Florence resumed its former stature as a capital of world sculpture, and when Ferdinando Marinelli received his training, the twentieth, when his company opened its doors, and the twenty-first century when the resources, experience, and casting quality make the Marinelli ‘Fonderia artistica’ unique in our time.

John T Spike

Florence, Italy

19 February 2007